2e partie, l’arrivée

C’est vers 1880 que s’est amorcé l’arrivée des premiers colons à Duhamel. À cette époque, le lac Long était déjà sous l’effet de la drave, créant ainsi l’île de la Pointe-à-Baptiste, avec une montée des eaux causée par l’écluse sur la rivière Petit-Nation. Sur une carte de 1884 (écluse aux épinettes) on y mentionne bien une écluse et non un barrage. Est-ce à dire que les draveurs pouvaient circuler entre la Chute de la Montagne et le lac Long, facilitant ainsi leur travail? En visitant le site de la « Dam à Tanascon », on y voit bien deux structures sur le lit de la rivière. Vous y trouverez aussi un panneau d’interprétation historique. Le site est situé à quelques dizaine de mètres du premier rapide de la rivière. Aussi accessible par un petit sentier en partance du chemin.

L’île de la Pointe-à-Baptiste était déjà habitée, probablement par Jean-Paptiste Bernard, un algonquin. Né en 1829 au lac Long, on le retrouve vivant sur sa ferme avec sa femme et ses quatre enfants en 1884. La carte ci-jointe (carte de l'arpenteur Mathieu, 1884) nous montre quatre bâtiments. En 1896, une autre carte, celle de l’arpenteur McLatchie nous donne plus de précision (Plan détaillé Pte-à-Baptiste). Comme mentionné dans la chronique précédente, il n’était pas seul à habiter au lac Kajakokanak (Long en algonquin). Simon Kanawato, celui qui donna son nom au lac Simon y vivait aussi, de même qu’Amable Canard blanc, du nom de l’île sur le lac Simon.

C’est aussi probablement le même Jean-Baptiste ou son fils Jean qui a donné son nom à la petite île de roche à l’embouchure de la rivière Petite-Nation, la Roche-à-Jean. Selon les récits de l’époque, une femme accompagnant les draveurs lors d’un voyage de bois, fut effrayée par un violent orage qui s’était levé sur le lac Gagnon. Pouvant difficilement manœuvrer le bateau avec l’estacade de bois qu’il traînait, elle fut laissée avec un indien du nom de Jean sur l’îlot pour la nuit On vint les rescaper le lendemain. L’histoire de cette femme vient de mon grand-père. Il parlait alors de sa mère. C’est la même histoire qu’on raconte au village. Une ancre de bateau a été retrouvée près de l’île et installée à l’entrée du village à Duhamel.

Avant la naissance de tout village, il y a d'abord l'arrivée de gens, qui, dans l’espérance d'une vie meilleure, décident d'aller s'implanter dans une région qui leur paraît favorable, soit par ce qu'ils en ont entendu parler, soit parce que les autorités décident de coloniser une région et de donner des terres, soit parce qu'ils pensent y trouver du travail et d'y fonder une famille. Ou tout simplement mais plus rarement par goût de l'aventure. À la fin du 19e siècle, la vie de tous les jours était déjà une aventure pour la plupart des gens ordinaires.

Alors que les premiers arpentages d’exploration se terminent, le lac Long est administrativement divisé en deux territoires, le canton Gagnon et le canton Preston. Duhamel s’appelle alors Preston. Les premiers colons à venir s’établir à Duhamel et au lac Long le feront à partir des années 1880. Le chemin menant au lac Long, appelé alors « chemin Mercier » sur certaines cartes, était rudimentaire. C’était plutôt un chemin de chantier… Car ce qui attirait les colons qui venaient s’établir, c’était la possibilité de travailler dans les chantiers l’hiver et sur une ferme le printemps venu.

Un des premiers à venir s’établir au lac Long fut le Rév. Amédée Thérien, chapelain de l’école de réforme de Montréal, connue aussi sous le nom de Mont St-Antoine. Arrivé en septembre 1880 avec quelques jeunes adultes ou ados dans l’espoir de les « réformer » en les intéressant à l’agriculture, il s’installa à l’embouchure de la rivière en face de la presqu’île. Il apportait avec lui quelques deux mille plants de vigne qu’il planta sur l’île dans l’espoir d’y produire du vin. Malgré ses efforts louables, ces jeunes colons veulent tout abandonner. Il ne reste aujourd’hui que le nom de l’Île-à-Raisins. Voici ce que raconte l’abbé Proulx lors d’une expédition de 8 personnes au lac Long pour visiter la jeune colonie (Voyage au lac Long, Rév. J.B. Proulx, Imprimerie du nord, 1882). Elle est composée du Rév. J.B. Proulx, d’Amédée Thérien, chef de l’expédition, de sa mère, Mme Pierre Thérien qui veut rendre visite à son petit-fils, C. Gagnon, de son frère Olaüs Thérien, étudiant en droit, de J.B. Malboeuf qui fréquente le collège et qui vient pour se choisir des terres avec deux amis, d’un Irlandais, D. McNamara, étudiant en médecine et d’un élève de l’école de Réforme, M. Rodrigue, jeune homme costaud. Ils couchent à Saint-André-Avellin d’abord, au presbytère et à l’hôtel, puis à Hartwell (Chénéville). Le voyage se fait à partir de Montréal en train et ensuite en diligence à partir de Papineauville. Décrivant ce qu’il voit et ceux qu’ils rencontrent, ce court bouquin est intéressant à lire et décrit bien les mœurs de l’époque.

« La maison s'élève sur une pointe qui s'avance dans le lac, langue de terre qui peut contenir en superficie une douzaine d'arpents propres à la culture. Déjà, tout à l’entour, une clairière de trois arpents s'est faite jour à travers les sapins, les érables el les grands ormes dont les troncs énormes gisent sur le sol comme des géants vaincus et mutilés.

A quatre arpents en arrière, une montagne, haute de cent pieds, coupée à pic, sur le sommet de laquelle repose une couronne de beaux arbres met la demeure à l'abri des vents du nord et de l'ouest. Au flanc de la montagne, à cinquante pieds du sol, s'enfonce une grotte qui ressemble à une bouche entr'ouverte ; au-dessus s'avance perpendiculairement un bloc formé d'une seule pierre qui offre l'apparence d'un nez gigantesque: de là le nom de Butte-au-nez. »

J’ai bien essayé avec mon ami Gérard de retracer cette grotte, mais en hiver et en raquettes, avec beaucoup trop de neige au sol, nous n’y sommes pas parvenus. Ce n’est que partie remise!

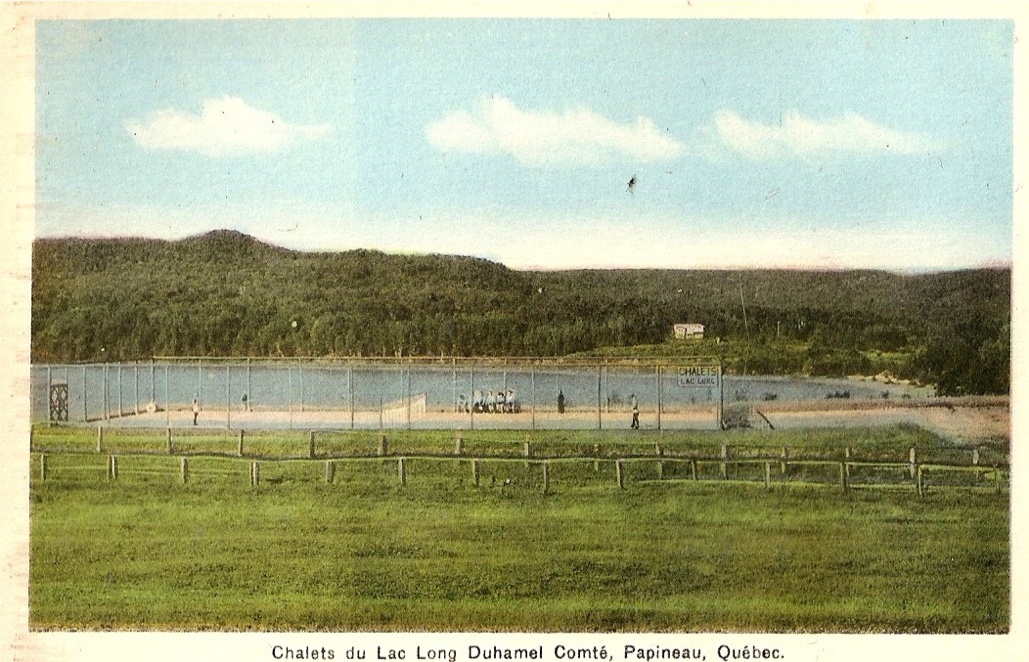

Mais même si les premiers colons à s’établir le long de la rivière n’obtiennent leurs titres qu’à partir de 1900, plusieurs sont arrivés dès 1882, dont Grégoire Carrière. Ce fut presqu’exclusivement au sud du lac et allant jusqu’à la Pointe-à-Baptiste que les premiers lots furent alloués. On y retrouve les noms de Joseph Carrière (1893), Louis Tanascon (1901), Georges et Émilien Chartrand (Eh oui, mon arrière-grand père et son père Émilien, 1902), Joseph Émard (1901), et plus tard, Arthur Lamontagne (1919), Lucia Delorme (1930). Ce dernier lot situé à droite de l’ancien camping Poliquin, deviendra plus tard un lieu de villégiature important à partir de 1940.

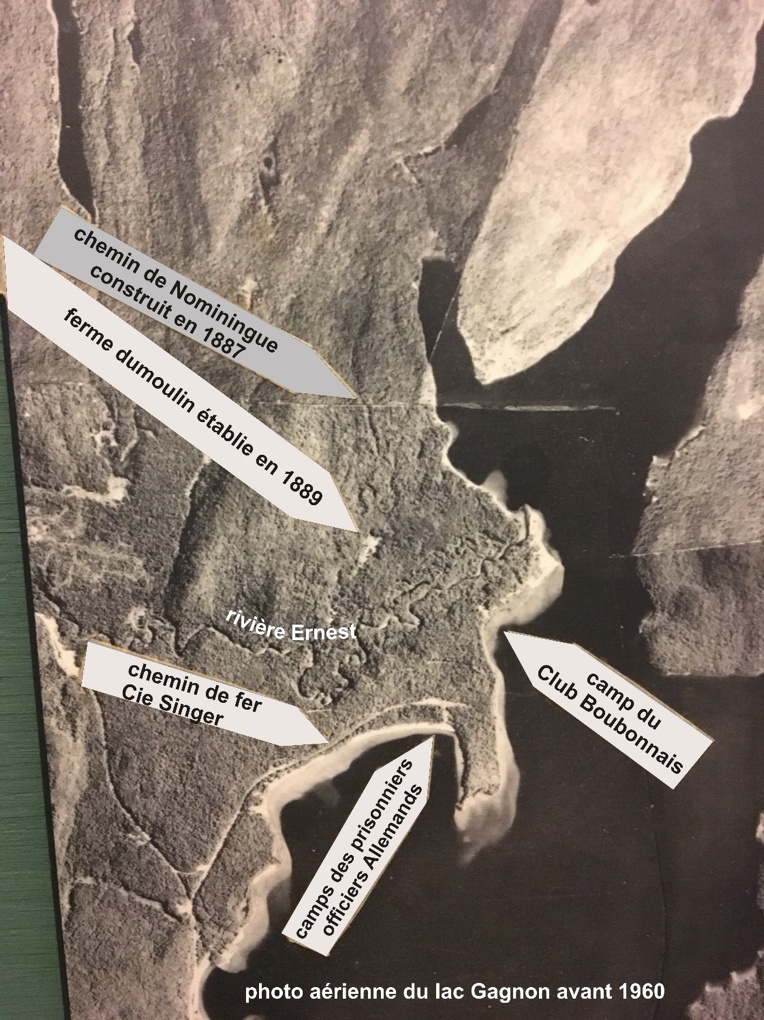

En 1887, un chemin (carte arpentage chemin de colonisation) fut construit entre Duhamel et Nominingue afin de relier la région d’Ottawa avec les Hautes Laurentides, dans le but de favoriser la colonisation, alors encouragée par le curé Labelle. Ce chemin, dont certains tronçons existent encore intégralement, comme le sentier Le Chemin du Roi (Club Skira, carte des pistes) aura coûté 12,447.08$ plus 5000$ pour l’exploration!

En 1887, un chemin (carte arpentage chemin de colonisation) fut construit entre Duhamel et Nominingue afin de relier la région d’Ottawa avec les Hautes Laurentides, dans le but de favoriser la colonisation, alors encouragée par le curé Labelle. Ce chemin, dont certains tronçons existent encore intégralement, comme le sentier Le Chemin du Roi (Club Skira, carte des pistes) aura coûté 12,447.08$ plus 5000$ pour l’exploration!

Dès 1889, un premier colon en partance de Nominingue, Maxime Dumoulin, vint s’établir avec ses 8 garçons et une fille presqu’à l’embouchure de la rivière Ernest, appelée alors le Creek Simon. L’emplacement de sa ferme, encore visible plus de cent ans plus tard, a été chambardée lors de la coupe forestière qui a suivi la tornade de 2006.

Dans une prochaine chronique, nous verrons l’arrivée du chemin de fer et la venue des premiers touristes au Lac Long, soit la période 1930-1960.